Table of Contents

- Background: The Alabuga Recruitment Drive

- How the Scheme Worked

- Inside the Factory: Working Conditions

- Human-rights and Legal Concerns

- Responses and Investigations

- Why This Matters Globally

- Conclusion: Accountability and Repair

By The Morning News Informer — Updated November 8, 2025

Background: The Alabuga Recruitment Drive

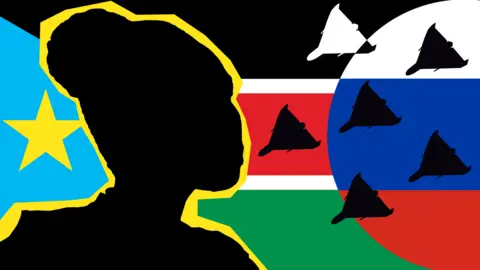

Over the past two years a recruitment programme called Alabuga Start quietly targeted young women across Africa with promises of scholarships, vocational training and well-paid work in Russia. In reality, a growing number of testimonies show that African women Russian drone factories is not a sensational headline but a stark description of what many recruits found upon arrival: they were placed inside production lines for military drones, often without clear consent and under dangerous conditions.

Sponsored adverts — sometimes even appearing to carry the imprimatur of local ministries — pushed opportunities to 18–22-year-olds seeking training in logistics, hospitality and technical trades. For many, the promise of exposure, a stable salary and new skills was irresistible. Instead, several recruits say they were channeled into factories producing Shahed-style drones, a step that has now prompted international concern about deception, labour exploitation and complicity in a war economy.

How the Scheme Worked

Applicants were typically asked to submit basic personal details and their preferred field of training. Recruitment took months, involving visa processing and pre-departure orientation. Once in Russia, however, the picture often changed. Workers describe being given uniforms and told to report for their assigned station — without the chance to decline factory placements. Those who asked questions were reminded of non-disclosure agreements they had signed and warned about penalties for “breach of contract.”

A number of social-media influencers from South Africa and elsewhere promoted the scheme; their endorsements made the programme appear legitimate and aspirational. Yet evidence gathered by BBC reporters, corroborated by interviews with former participants, shows a pattern of withheld information, withheld passports at times, and pay far lower than advertised — conditions consistent with coercive labour practices.

Inside the Factory: Working Conditions

Once placed on the assembly lines, recruits who believed they would be learning hospitality or crane operation found themselves in halls full of drone frames, wiring harnesses and motor components. Several former workers told investigators they were required to handle solvents, adhesives and paints without adequate protective equipment — or that supplied gear quickly degraded and became ineffective.

One young woman described how the solvents made her protective suit stiff and how, within days, her skin began to peel. Hospital visits, chemical burns and repeated respiratory irritation were reported. These first-hand accounts paint a picture of industrial safety standards that fall short of international norms, particularly for work that involves toxic substances and precision electronics.

Beyond chemical exposure, recruits described gruelling schedules, strict disciplinary fines, and deductions from wages for minor infractions. Several reported receiving only a fraction of the salary promised in recruitment adverts after rent, classes and other “fees” were deducted. When some women attempted to leave after learning what they were doing, organisers sometimes confiscated passports or made it difficult to secure a return ticket — a hallmark of exploitative labour schemes.

Human-rights and Legal Concerns

The combination of deception in recruitment, hazardous working conditions, restricted freedom of movement and wage manipulation raises obvious human-rights red flags. Human-rights groups and legal experts have pointed to elements consistent with forced labour or trafficking offences. The presence of NDAs and disciplinary clauses that penalise workers for speaking out compounds the difficulty of reporting abuses or seeking remedy.

From an international-law perspective, the allegation that civilians were coerced into manufacturing weapons used in an active conflict introduces another layer of concern: it blurs the lines between civilian labour and direct support for military operations. While some companies in Russia have openly acknowledged production of Iranian-design drones at Alabuga, the recruitment of foreign nationals under false pretences suggests potential violations of migration, labour and criminal statutes in multiple jurisdictions.

Responses and Investigations

The revelations prompted swift reactions. South African authorities have opened inquiries and issued warnings to citizens. International NGOs, including labour-rights organisations, have called for urgent investigations into recruitment channels and corporate responsibility in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone. Russia’s Alabuga programme has denied systemic deception, stating that job fields are published and that salaries vary according to performance.

Media investigations, however, have exposed a patchwork reality: while some recruits reported relatively positive outcomes, many others described exploitation. The BBC documented multiple testimonies and corroborated elements of the story with footage and documents. Meanwhile, analysts at the Institute for Science and International Security and other monitoring bodies flagged the geopolitical implications of a foreign workforce contributing, even inadvertently, to drone production.

Legal avenues remain complex. Jurisdictional limits, the mobility of alleged perpetrators, and the reluctance of some victims to testify publicly (fearing reprisals or stigma) complicate efforts to secure accountability. Still, international pressure — diplomatic inquiries, travel advisories and criminal probes — has increased scrutiny on both recruiters and host firms.

Why This Matters Globally

The story of African women Russian drone factories matters for several reasons, each pointing to broader systemic risks:

- Human-rights protection: The apparent use of deception and coercion highlights persistent vulnerabilities in recruitment channels for migrant labour, especially among young women from economically marginalised regions.

- War economy accountability: When civilian labour is used to produce weapons, even unknowingly, it raises ethical and legal questions about corporate complicity and supply-chain oversight.

- Migration governance: The case underscores how state-backed or state-tolerated programmes can mask exploitative labour flows, suggesting a need for stronger consular protections and pre-departure verification by sending states.

- Public health: Exposure to hazardous chemicals without proper safety measures creates long-term medical needs that host and sending countries must address.

For communities in source countries, the fallout is profound. Families who believed a relative had secured legitimate training now face the emotional and financial consequences of exploitation. For international civil society, the episode is a clarion call to tighten oversight, support survivors and dismantle recruitment networks that rely on false advertising and social-media influencers to legitimise risky schemes.

Conclusion: Accountability and Repair

The Alabuga revelations are a painful reminder that globalisation of labour can be a force for good African women Russian drone factories— or a pathway to exploitation. The phrase African women Russian drone factories encapsulates both a headline and a human story: young lives upended by false promises, and labour used in service of a conflict with grave human costs.

What comes next must be multifaceted. Sending states should expand pre-departure checks and public awareness campaigns African women Russian drone factories; international bodies and NGOs must document abuses and provide legal and medical support to survivors; and companies operating in special economic zones must be held to binding standards of transparency and worker protection. In the longer term, dismantling the recruitment chains that led young women from South Sudan and beyond into hazardous work will require political will, cross-border cooperation, and resources dedicated to victim assistance and prevention.

The women who spoke out — like Adau, whose account helped reveal the scale of the problem — deserve restitution and protection. Their testimony has pulled back a curtain on a troubling nexus of labour exploitation, war production and opaque recruitment. Recognising this, acting on it and ensuring survivors can rebuild are the first steps toward accountability.