When India Almost Moved Away from Parliamentary Democracy

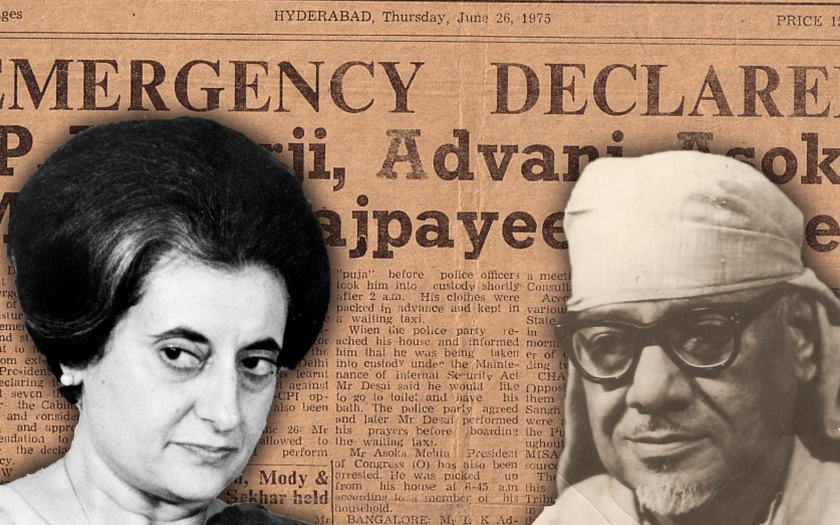

During the mid-1970s, India underwent one of its most turbulent political phases under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Emergency rule (1975-1977) presidential. Civil liberties were suspended, political opposition jailed, and behind closed doors, there was a serious push to reimagine India’s democracy—not as a parliamentary system rooted in checks and balances, but as a centralized presidential state.

The Emergency and the Push for Centralized Power

Historian Srinath Raghavan reveals in his book Indira Gandhi and the Years That Transformed India that Gandhi’s loyalists and top bureaucrats advocated for a presidential system inspired by Charles de Gaulle’s France. This system would grant sweeping powers to a directly elected president, weaken the judiciary, and marginalize Parliament to a largely symbolic role.

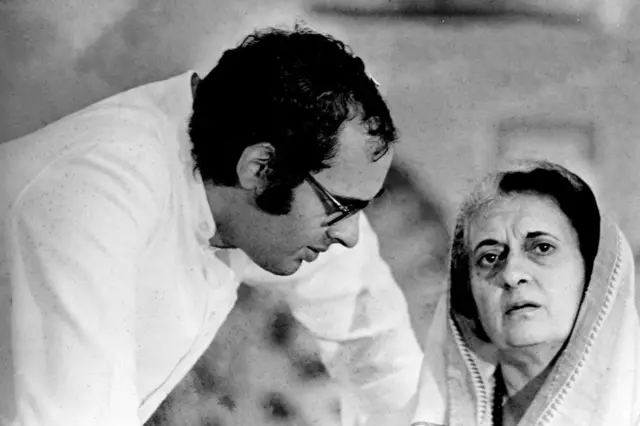

Senior diplomat BK Nehru, a close aide to Gandhi, was a key proponent. Writing in 1975, he described the Emergency as a moment of “immense courage and power” and urged the prime minister to seize the opportunity to introduce a seven-year presidential term, curtail judicial power, and impose stricter controls on the press.

The Drafting of Authoritarian Constitutional Changes

These ideas materialized into a secret document titled “A Fresh Look at Our Constitution: Some Suggestions” proposing a president with even greater powers than the American model, including control over judicial appointments and legislative interpretation. Though never formally proposed, this plan influenced the Forty Second Amendment Act of 1976, which centralised power in the executive, limited judicial review, and expanded Parliament’s authority.

This amendment also extended the federal government’s ability to impose President’s Rule in states and restrict election disputes from judicial scrutiny—marking a significant tilt toward authoritarianism.

Resistance and the Return to Democracy

While some Congress leaders, including Haryana’s chief minister and defence minister Bansi Lal, openly called for “lifelong power” for Gandhi, others like Tamil Nadu’s M Karunanidhi opposed the idea. Gandhi herself remained non-committal, ultimately prioritizing quick passage of the amendment without fully committing to the presidential system.

The Emergency ended with Gandhi’s defeat in 1977. The Janata Party reversed many of the authoritarian provisions through subsequent constitutional amendments, restoring democratic norms and judicial independence.

The Presidential Temptation Returns

In 1982, Gandhi briefly considered resigning as prime minister to become India’s president, a role that could have given her a different kind of power and allowed her to “shock” her party into renewal. Ultimately, she withdrew and instead elevated her loyal home minister Zail Singh to the presidency.

Why India Stayed Parliamentary

The flirtation with a presidential system reflected frustration with parliamentary instability and a desire for strong executive authority during times of crisis. However, lack of broad political support, Gandhi’s cautious pragmatism, and India’s entrenched democratic traditions prevented the shift.

After Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, momentum for such a radical change vanished. India remains one of the world’s largest functioning parliamentary democracies, shaped by this near-miss with authoritarian presidentialism.